In film, short doesn’t mean easy

Charlie, a locally produced movie about autism, seeks support from the community

From The Orlando Weekly, March 27, 2013

When trying to create a movie, the old adage is if you can’t go long, go short, at least until you can build support for a feature-length production. Yet that often belies the fact that a short film can be a complex and costly undertaking in its own right.

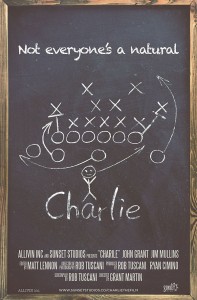

Case in point: Charlie, the little local film that could, or at least is trying to. The movie will tell the story of an autistic teenager and his football-coach dad, who is struggling to deal with his son’s condition. It’s being produced by Sunset Studios, an Orlando production company founded last year by Ryan and Cristina Cimino, who intend to finance the 20-minute project for just $2,500 – because almost everything is being donated and everyone is working for free. (Food, basic supplies and a mandatory general-liability policy are the only major expenses.) Still, the complicated process has already taken many months, with no footage to show for it yet. That should finally change in April, when the weeklong shoot is planned.

Case in point: Charlie, the little local film that could, or at least is trying to. The movie will tell the story of an autistic teenager and his football-coach dad, who is struggling to deal with his son’s condition. It’s being produced by Sunset Studios, an Orlando production company founded last year by Ryan and Cristina Cimino, who intend to finance the 20-minute project for just $2,500 – because almost everything is being donated and everyone is working for free. (Food, basic supplies and a mandatory general-liability policy are the only major expenses.) Still, the complicated process has already taken many months, with no footage to show for it yet. That should finally change in April, when the weeklong shoot is planned.

To find the project’s origins, you have to go back to a news story from 2006.

“I was watching a newscast of a young man that has autism,” Rob Tuscani, the film’s writer, cinematographer and co-producer says. “He was a water boy on a basketball team, and the last game of the season they put him in. … He shot like six three-pointers. I started balling my eyes out, watching this kid, and I thought, wow, you know, what would it be like to have this son that was, you know, perhaps a tremendous athlete, but [the dad is a] really awful person and said, you know, ‘To hell with my son. I don’t want to have anything to do with him.’”

Director Grant Martin, creator of the 8-minute The Cab, which played Enzian’s FilmSlam showcase last July, is himself still a student (at Full Sail University). He was invited into the project by his mentor, Tuscani, with whom he had worked before.

“It’s a love story between father and son, and it’s because of Charlie’s condition that Harlin, the father [experienced local actor Jim Mullins], has to condition himself to face, sort of, his past and himself,” Grant says. “[Autism] is a tough topic, and I think because we’re bringing that value into somebody who is so young, that’s just gonna be a real challenge, but it’s gonna be very fun and very memorable.”

The project has already benefitted from its subject, as autism awareness was perhaps the main reason the film drew close to 100 people to a fundraiser on February 15 at 310 Lakeside café and bar in downtown Orlando. The public was invited, for $25 a person. In exchange, donors were treated to food, drink, prizes, information about the movie and a speech by Dr. Andrew Pittington, an expert in social disorders.

“I think this movie touches on such a wonderful component,” Pittington says. “Autism itself is not a one-size-fits-all condition. … I know [someone like] Charlie. … I have Charlie [as a patient]. He sees me every week. … Charlie lives amongst us every single day, and I guarantee Charlie’s dad lives amongst us, and we need to help him too.”

Despite the good will, and about $1,300, generated by the fundraiser, it should be noted that none of the profits – if there are any, which is rare for a film like this – will go to charity.

“In asking the community to support the fundraiser, we again let folks know what the film was about and created an event that gave something back to them for their support,” says Ryan Cimino. “[But] we did not reach out to organizations in the community that support autism. Most of them have their hands and schedules full, not to mention that they campaign for support in a different way.”

With or without the support of such organizations, can Cimino really produce this film for just $2,500? Maybe, says Tim Anderson, local filmmaker and programming director of FilmSlam, but only because Cimino isn’t paying for actors, technicians and equipment.

“Their budget is basically covering craft services and whatever incidentals they might need,” Anderson speculates. “You still have to have insurance on your shoot, so that’s probably about $400 a day. … You can still do it for $2,500.”

Shooting on private property is best, Anderson says, as is keeping the locations to a minimum. And Charlie is certainly doing that, since a football field, a house and a hospital will be the only sets.

Tuscani has secured an Arri Alexa digital camera and related equipment, similar to the ones used on Skyfall and Hugo, for free, which he says will save $6,000-$8,000. That’s admittedly a great accomplishment, but it’s no safeguard against what Anderson describes as the greatest potential pitfall.

“The biggest problem with a short film, if you can get all the technical fundamentals down, … is bad acting and bad line delivery,” Anderson says. “There’s no reason whatsoever in the digital age to capture a bad performance. … You should be able to shoot until they get it right. It doesn’t cost. We’re not Stanley Kubrick-ing like a million feet of film.”

Tuscani agrees that films, be them short or feature-length, are fraught with difficulties. “It looks so easy and seamless when you go and watch a film, but it is extremely difficult,” he says. “There are so many challenges along the way, be it locations, be it insurance, be it the proper talent, be it the music.”

New filmmakers could learn a lot from Charlie: Keep your budget small by seeking donations, find talented people who will work for little or no money, and pick a topic that might gain support within the community. And be prepared for the process to last longer than you expect. In the case of Charlie, that will likely be at least a year, once post-production is done and this unique project is finally ready for submission to film festivals.

© 2013 Orlando Weekly / MeierMovies, LLC