Loving Vincent

Loving Vincent, 2017, 4 ¾ stars

Moving pictures

Loving Vincent is this century’s best animated film

From The Orlando Weekly, October 4, 2017

Oil painting was arguably the dominant visual art form for nearly 500 years before being supplanted in the early 20th century by film. But no one has had the courage to fully combine the two mediums until now.

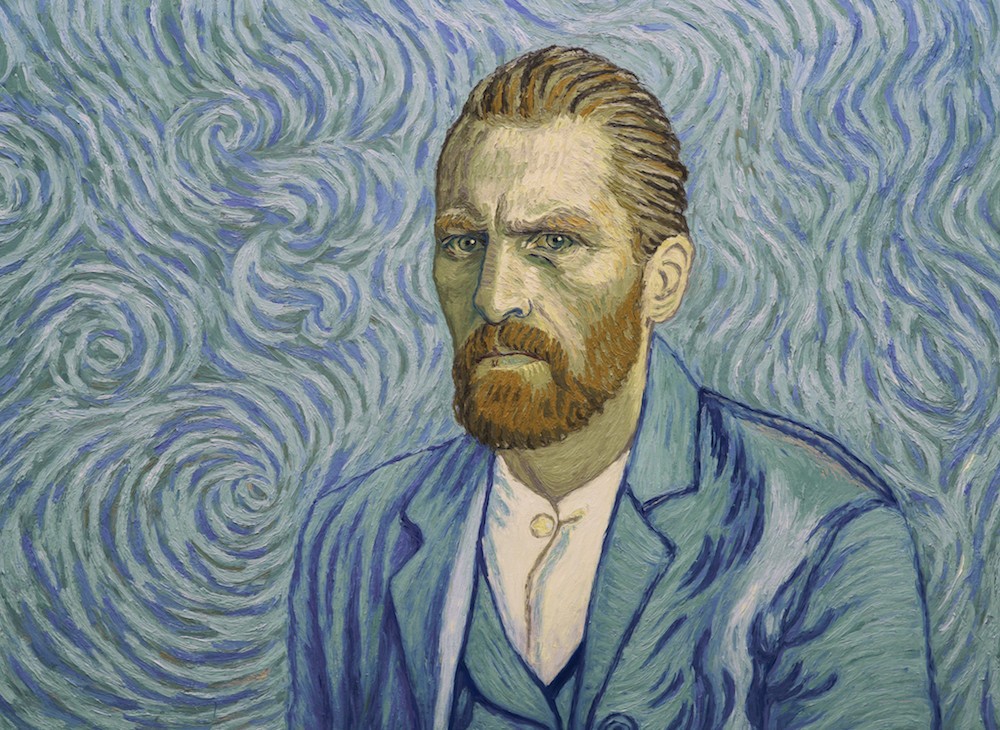

Loving Vincent, an astonishingly beautiful new movie about the life and death of Vincent van Gogh, is the brainchild of Polish filmmaker Dorota Kobiela, who directed it with English moviemaker Hugh Welchman and wrote it with Welchman and fellow Pole Jacek Dehnel. It took them and a team of more than 100 artists over six years to hand-paint the film’s 65,000 frames. The wait was worth it, as their creation is the best animated film of this century and the most nobly conceived of all time.

Though each painting is an original composition, the artists had help. For the characters (almost all of which are based on the real people in Van Gogh’s paintings), the filmmakers started with old-fashioned rotoscoping, the process of filming live action and painting over it. Purists might call it cheating, but it’s been used by the likes of Walt Disney (for the dance sequences in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) to produce breathtakingly realistic movement. But even with rotoscoping, the artists still had to paint everything, including the landscapes, which were inspired by Vincent’s paintings. Seeing his masterpieces come to life is almost a religious experience for Van Gogh fans.

The story, though a tad straightforward, is almost as entertaining as the art. Set in 1891 (one year after Vincent’s death), the screenplay examines the mysterious circumstances of Vincent’s supposed suicide by introducing us to the people the artist knew in Paris, Arles and Auvers, France. These are the men, women and children who inhabited his paintings and letters, and the plot – though fictional – feels like a true-life detective story.

The detective is not a detective at all but a cantankerous drunkard named Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth). Though Armand knew Vincent, he shows little interest in solving the mystery of the artist’s death when first approached by his father, Joseph (Chris O’Dowd). Joseph was Vincent’s mailman and close friend, and when he discovers that one of the final letters Vincent wrote to his brother Theo has gone undelivered, he convinces his son to deliver it in person. But after Armand discovers that Theo too has died and everyone he meets has a different take on Vincent’s death, he is transformed, and his quest to deliver the letter (a classic Hitchcock MacGuffin) turns into a journey of self-discovery.

If this all sounds a bit like The Third Man, it is, complete with numerous noir-style flashbacks painted in gorgeous black and white. You shouldn’t expect Vincent to turn up alive like Harry Lime, but you can look forward to a rebirth of his spirit.

The movie is well scored by Clint Mansell (known for his Darren Aronofsky compositions), surprisingly fast paced and affectionately acted. (Saoirse Ronan, Jerome Flynn, Helen McCrory, John Sessions, Eleanor Tomlinson and Robert Gulaczyk – as Vincent – are all pitch perfect.) Indeed, this was obviously a passion project for everyone involved, including the co-directors, who fell in love during the production. After watching their film, you might just fall in love too.

“We cannot speak other than by our paintings,” Van Gogh wrote. This movie practically bellows, and its message about love, life and art is heard loud and clear, even if you have but one ear.

© 2017 Orlando Weekly / MeierMovies, LLC

For other art-themed films, see this 2006 article.