Existential opposites

A life of nothing and a life of everything

Exclusive to MeierMovies, November 29, 2025

Exclusive to MeierMovies, November 29, 2025

Spoiler alert: This article includes extensive plot details, so you might wish to watch the films first.

I wrote an article last year comparing Forrest Gump and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Though the movies share similar stories and Eric Roth penned both screenplays, they are essentially opposites: Forrest is an unremarkable man leading a remarkable life while Benjamin is a remarkable man leading an unremarkable life.

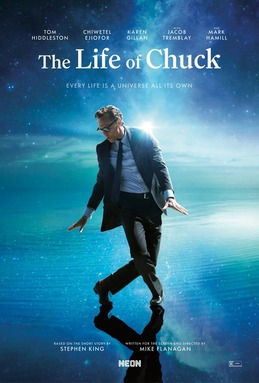

Director Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams (3 ½ stars) and director Mike Flanagan’s The Life of Chuck (3 ¾ stars), both released this year, have a similarly odd relationship. Based on novellas, each film recounts almost the entire life of its subject – childhood, career, marriage, children, search for meaning – partially through voiceover narration. But that’s where the similarities end, as Robert from Train Dreams seemingly lives a life of nothing while Chuck lives a life of almost everything.

During his early years in the Pacific Northwest during the first half of the 20th century, Robert (Joel Edgerton, in perhaps his best performance) lives an unfulfilled and empty life, until he meets his wife (Felicity Jones), with whom he has a daughter. But after they are both killed in a devastating forest fire, Robert is adrift and alone, haunted by their deaths and his disturbing experiences as a railway worker. Though he manages to find some perspective or meaning in the meaningless toward the end of the film, Train Dreams is that rare movie exploring a person whose life never amounts to much. No big dreams. No major accomplishments. Just existence.

In contrast, Chuck (Tom Hiddleston) is the entire world, literally. As he lies dying in the hospital from a brain tumor, all the other characters in the first part of the film – in a fantastical premise – face the end of their world. Chuck’s brain, as Walt Whitman wrote, “contains multitudes,” meaning Chuck has populated his death-bed dream with people he has met throughout his life and given them stories that mean something to him. So when he dies, they die.

In contrast, Chuck (Tom Hiddleston) is the entire world, literally. As he lies dying in the hospital from a brain tumor, all the other characters in the first part of the film – in a fantastical premise – face the end of their world. Chuck’s brain, as Walt Whitman wrote, “contains multitudes,” meaning Chuck has populated his death-bed dream with people he has met throughout his life and given them stories that mean something to him. So when he dies, they die.

“We know that a dream can be real, but whoever thought that reality could be a dream? We exist, of course, but how, in what way? As we believe, as flesh-and-blood human beings? Or are we simply parts of someone’s feverish, complicated nightmare?”

That epilogue from “Shadow Play,” an episode of The Twilight Zone from 1961, likely served as an inspiration for The Life of Chuck, or perhaps the Stephen King novella on which it is based. In that TW story, Dennis Weaver plays a death-row inmate about to be electrocuted – in his own nightmare. And, like Chuck, he populates his dream world with real people from his life. So when the lever on the electric chair is pulled, the universe ends.

Both films do a wonderful job exploring identity, so maybe they aren’t polar opposites after all. Instead, perhaps they are just different sides of the same coin, as both have a lot to say about the roles we play, or think we play. But there is still another film from this year that adds even more to that conversation, and it’s an arguably the best of all three.

Rental Family (4 stars) begins as a deceptively simple, sweet and funny story of an American, Phillip (Brendan Fraser), living in Tokyo, who takes a job with a company that places actors in real situations. Need a friend to play video games with you? Need a woman to stand in as your mistress and apologize to your wife for the infidelity? Need a temporary father for your child? Rental Family to the rescue.

Rental Family (4 stars) begins as a deceptively simple, sweet and funny story of an American, Phillip (Brendan Fraser), living in Tokyo, who takes a job with a company that places actors in real situations. Need a friend to play video games with you? Need a woman to stand in as your mistress and apologize to your wife for the infidelity? Need a temporary father for your child? Rental Family to the rescue.

But as the story progresses, it slowly opens doors you didn’t think it had, exposing lives unled, or unfulfilled, or just plain fake. It has the courage to ask – in an otherwise lighthearted film – what it means to interact with fellow humans and how the roles we play in life shape our reality and pseudo-reality. Writer-director Hikari’s Rental Family may not be as good as Fraser’s 2022 triumph, The Whale, but it offers a whale of an existential commentary.

In Rental Family’s final scene, Phillip visits the shrine that one of his “family members” frequented, looking for the same answers that his make-believe friend found at the end of his life. But there are no easy answers. No gods. Just a mirror. The answers that Phillip, and Robert, and Chuck, and we seek lie within ourselves.

© 2025 MeierMovies, LLC